During these days of practice together, we've been reading the names of many people - our departed loved ones, and also relatives, family members, friends, who are suffering untold agony and hardship at this time. There is so much misery all around us - how do we accept it all? We've heard of suicides, cancer, aneurysms, motor neurone disease - plucking the life out of so many young and vibrant people. And old age, sickness, decay and death snuffing the life out of many elderly people who still have a lot of living that they want to do. Why does this happen?

Death is all around us in nature. We're coming into the season now where everything is dying. This is the natural law, it's not something new. And yet time and again we keep pushing it out of our lives, trying our best to pretend that we're not going to die - that we won't grow old, that we'll be healthy, wealthy and wise until the last moment.

We are constantly identified with our bodies. We think, "This is me", or, "I am my body, I am these thoughts. I am these feelings, I am these desires, I am this wealth, these beautiful possessions that I have, this personality." That's where we go wrong. Through our ignorance we go chasing after shadows, dwelling in delusion, unable to face the storms that life brings us. We're not able to stand like those oak trees along the boundary of the Amaravati meadow - that stay all winter long and weather every storm that comes their way. In October, they drop their leaves, so gracefully. And in the spring, they bloom again. For us too there are comings and goings, the births and deaths, the seasons of our lives. When we are ready, and even if we are not ready, we will die. Even if we never fall sick a day in our lives, we still die; that's what bodies are meant to do.

When we talk about dying before we die, that does not mean that we should try to commit suicide to avoid suffering; it means that we should use this practice, this way of contemplation, to understand our true nature. In meditation we can go deeply into the mind, to investigate: who is it that we really are?Who dies?... Because what dies is not who we are.

Death can be peaceful. A peaceful death is a gift, a blessing to the world; there is simply the return of the elements to the elements. But if we have not come to realise our true nature, it can seem very frightening, and we might resist a lot. But we can prepare ourselves, by investigating who it is that we really are; we can live consciously. Then when the time comes, we can die consciously, totally open, just like the leaves fluttering down, as leaves are meant to do.

Chasing shadows... What is it that we are really looking for in life? We're looking for happiness, for a safe refuge, for peace. But where are we looking for these things? We desperately try to protect ourselves by collecting more and more possessions, having to have bigger and bigger locks on the door, putting in alarm systems. We are constantly armouring ourselves against each other - increasing the sense of separation - by having more possessions, more control, feeling more self-importance with our college degrees, our PhD's. We expect more respect, and we demand immediate solutions; it is a culture of instantaneous gratification. So we're constantly on the verge of being disappointed - if our computer seizes up, if we don't make that business deal, or if we don't get that promotion at work.

This is not to put down the material realm. We need material supports, food, clothing, medicines; we need a shelter and protection, a place to rest; we also need warmth, friendship. There's a lot that we need to make this journey. But because of our attachment to things, and our efforts to fill and fulfil ourselves through them, we find a residue of hunger, of unsatisfactoriness, because we are looking in the wrong place. When somebody suddenly gets ill, loses a leg, has a stroke, is faced with death, gets AIDS and has to bear unspeakable suffering, what do we do?Where is our refuge?

When the Buddha was still Prince Siddhartha before his enlightenment, he had everything. He had what most people in the world are running after, as they push death to the edge of their lives, as they push the knowledge of their own mortality to the farthest extreme of consciousness. He was a prince. He had a loving wife and a child. His father had tried desperately to protect him from the ills of life, providing him with all the pleasures of the senses, including a different palace for every season. But he couldn't hold his son back, and one day the Prince rode out and saw what he had to see: the Four Heavenly Messengers.

Some of us might think it's contradictory that a heavenly messenger could come in the form of a very sick person: "What's so heavenly about a very sick person?" But it is a divine messenger, because suffering is our teacher, it's through our own experience and ability to contemplate suffering that we learn the First Noble Truth.

The second and third messengers were a very old man struggling along the roadside, and a corpse, riddled with maggots and flies, decaying on the funeral pyre. These were the things the Buddha saw that opened his eyes to the truth about life and death. But the fourth heavenly messenger was a samana, a monk; a symbol of renunciation, of someone who'd given up the world in order to discover the Truth within himself.

Many people want to climb Mount Everest, the highest mountain in the world, but actually there is a Himalaya in here, within each of us. I want to climb that Himalaya; to discover that Truth within myself, to reach the pinnacle of human understanding, to realise my own true nature. Everything on the material plain, especially what we seem to invest a lot of our energy hungering for, seems very small and unimportant in the face of this potential transformation of consciousness.

So that's where these four celestial signs were pointing the young Siddhartha. They set him on his journey. These are the messengers that can point us to the Way of Truth and away from the way of ignorance and selfishness, where we struggle, enmeshed in wrong view, unable to face our darkness, our confusion, our pain. As Steven Levine said: "The distance from our pain, from our wounds, from our fear, from our grief, is the distance from our true nature."

Our minds create the abyss - that huge chasm. What will take us across that gap? How do we get close to who we really are - how can we realise pure love in itself, that sublime peace which does not move towards nor reject anything? Can we hold every sorrow and pain of life in one compassionate embrace, coming deeply into our hearts with pure awareness, mindfulness and wise reflection, touching the centre of our being? As we realise who we are, we learn the difference between pain and suffering.

What is grief really? It's only natural that when someone we are close to dies, we grieve. We are attached to that person, we're attached to their company, we have memories of times spent together. We've depended on each other for many things - comfort, intimacy, support, friendship, so we feel loss.

When my mother was dying, her breath laboured and the bodily fluids already beginning to putrefy, she suddenly awoke from a deep coma, and her eyes met mine with full recognition. From the depths of Alzheimer's disease that had prevented her from knowing me for the last ten years, she returned in that moment to be fully conscious, smiling with an unearthly, resplendent joy. A radiance fell upon both of us. And then in the next instant she was gone.

Where was the illness that had kidnapped her from us for so many years? In that moment, there was the realisation of the emptiness of form. She was not this body. There was no Alzheimer's and 'she' was not dying. There was just this impermanence to be known through the heart and the falling away, the dissolution of the elements returning to their source.

Through knowing the transcendent, knowing who we really are – knowing the body as body - we come to the realisation that we are ever-changing and we touch our very essence, that which is deathless. We learn to rest in pure awareness.

In our relationships with each other, with our families, we can begin to use wisdom as our refuge. That doesn't mean that we don't love, that we don't grieve for our loved ones. It means that we're not dependent on our perceptions of our mother and father, children or close friends. We're not dependent on them being who we think they are, we no longer believe that our happiness depends on their love for us, or their not leaving, not dying. We're able to surrender to the rhythm of life and death, to the natural law, the Dhamma of birth, ageing, sickness and death

When Marpa, the great Tibetan meditation master and teacher of Milarepa, lost his son he wept bitterly. One of his pupils came up to him and asked: "Master, why are you weeping? You teach us that death is an illusion." And Marpa said: "Death is an illusion. And the death of a child is an even greater illusion."

Marpa showed his disciple that while he could understand the truth about the conditioned nature of everything and the emptiness of forms, he could still be a human being. He could feel what he was feeling; he could open to his grief. He could be completely present to feel that loss.

There is nothing incongruous about feeling our feelings, touching our pain, and, at the same time understanding the truth of the way things are. Pain is pain; grief is grief; loss is loss - we can accept those things. Suffering is what we add onto them when we push away, when we say, "No, I can't."

Today, while I was reading the names of my grandparents who were murdered, together with my aunts and uncles and their children, during World War II - their naked bodies thrown into giant pits - these images suddenly overwhelmed me with a grief that I didn't know was there. I felt a choking pressure, unable to breathe. As the tears ran down my cheeks, I began to recollect, bringing awareness to the physical experience, and to breathe into this painful memory, allowing it to be. It's not a failure to feel these things. It's not a punishment. It is part of life; it's part of this human journey.

So the difference between pain and suffering is the difference between freedom and bondage. If we're able to be with our pain, then we can accept, investigate and heal. But if it's not okay to grieve, to be angry, or to feel frightened or lonely then it's not okay to look at what we are feeling, and it's not okay to hold it in our hearts and to find our peace with it. When we can't feel what must be felt, when we resist or try to run from life, then we are enslaved. Where we cling is where we suffer, but when we simply feel the naked pain on its own, our suffering dies... That's the death we need to die.

Through ignorance, not understanding who we are, we create so many prisons. We are unable to be awake, to feel true loving-kindness for ourselves, or even to love the person sitting next to us. If we can't open our hearts to the deepest wounds, if we can't cross the abyss the mind has created through its ignorance, selfishness, greed, and hatred, then we are incapable of loving, of realising our true potential. We remain unable to finish the business of this life.

By taking responsibility for what we feel, taking responsibility for our actions and speech, we build the foundation of the path to freedom. We know the result that wholesome action brings - for ourselves and for others. When we speak or act in an unkind way - when we are dishonest, deceitful, critical or resentful - then we are the ones that really suffer. Somewhere within us, there is a residue of that posture of the mind, that attitude of the heart.

In order to release it, to be released from it, we have to come very close. We have to open to every imperfection - to acknowledge and fully accept our humanity, our desires, our limitations; and forgive ourselves. We have to cultivate the intention not to harm anyone (including ourselves) by body, speech or even thought. Then if we do harm again, we forgive ourselves, and start from the beginning, with the right intention. We understand kamma; how important it is to live heedfully, to walk the path of compassion and wisdom from moment to moment - not just when we are on retreat.

Meditation is all the time. Meditation is coming into union with our true nature. The Unconditioned accepts all, is in total peace with all... total union, total harmony. As long as we're holding one negative thing in our hearts - towards ourselves or anyone else - we cannot fully realise our true nature. We cannot be free.

How can we really take responsibility for our actions? By reflecting on our virtuous, or wholesome actions we are taking responsibility, and this is a support for the practice in the present moment. We feel the momentum of our mindfulness, confidence, trust, the energy of purity of mind, and that helps us to keep going. Contemplating things that I don't feel good about can perhaps bring a dark cloud over consciousness. In fact this is very wholesome; it is the arising of moral shame and moral fear, hiri-ottappa. We know when we've done something that was not right, and we feel regret; being completely honest. But then we forgive ourselves, recollecting that we are human beings, we make mistakes. Through acknowledging our wrong action, our limitation, our weakness, we cross the abyss and free our hearts. Then we begin again.

This moral fear engenders a resolve in the mind towards wholesomeness, towards harmony; there is the intention not to harm. This happens because we understand that greed conditions more greed, and hatred conditions more hatred - whereas loving-kindness is the cause and condition for compassion and unity. Knowing this, we can live more skilful lives.

Once, when the Buddha was giving a teaching, he held up a flower. And the Venerable Mahakassapa, one of his great devotees and disciples, smiled. There's a mystery why the Venerable Mahakassapa smiled when the Buddha held up the flower.

What is it that we see in the flower? In the flower we see the ever-changing essence of conditioned forms. We see the nature of beauty and decay. We see the 'suchness' of the flower. And we see the emptiness of experience. All teachings are contained in that flower; the teachings on suffering and the path leading to the cessation of suffering -– on suffering and non-suffering. And if we bring the teachings to life in each moment of awareness, it's as if the Buddha is holding up that flower for us.

Why are we so afraid of death? It's because we have not understood the law of nature; we have not understood our true nature in the scheme of things. We have not understood that there's non-suffering. If there is birth, there is death. If there is the unborn, then there is that which is deathless: "The Undying, Uncreated, Love, the Supreme, the Magnificent, Nibbana."

In pain we burn but, with mindfulness, we use that pain to burn through to the ending of pain. It's not something negative. It is sublime. It is complete freedom from every kind of suffering that arises; because of a realisation - because of wisdom - not because we have rid ourselves of unpleasant experience, only holding on to the pleasant, the joyful. We still feel pain, we still get sick and we die, but we are no longer afraid, we no longer get shaken.

When we are able to come face to face with our own direst fears and vulnerability, when we can step into the unknown with courage and openness, we touch near to the mysteries of this traverse through the human realm to an authentic self-fulfilment. We touch what we fear the most, we transform it, we see the emptiness of it. In that emptiness, all things can abide, all things come to fruition. In this very moment, we can free ourselves.

Nibbana is not out there in the future; we have to let go of the future, let go of the past. This doesn't mean we forget our duties and commitments. We have our jobs and the schedules we have to keep, we have our families to take care of; but in every single thing that we do, we pay close attention, we open. We allow life to come towards us, we don't push it away. We allow this moment to be all that we have, contemplating and understanding things the way they really are - not bound by our mental and emotional habits, by our desires.

The candle has a light. That light, one little candle from this shrine can light so many other candles, without itself being diminished. In the same way, we are not diminished by tragedy, by our suffering. If we surrender, if we can be with it, transparent and unwavering - making peace with the fiercest emotion, the most unspeakable loss, with death - we can free ourselves. And in that release, there is a radiance. We are like lights in the world, and our life becomes a blessing for everyone.

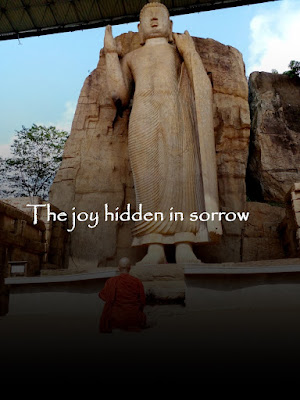

Jelaluddin Rumi wrote: "The most secure place to hide a treasure of gold is some desolate, unnoticed place. Why would anyone hide treasure in plain sight? And so it is said: 'Joy is hidden in sorrow.'"

The illumined master Marpa weeping over his child - does his experience of the loss of his young child diminish his wisdom? Or is it just the supreme humility of a great man, a great sage expressing the wholeness of his being, of his humanity.

I want to encourage each one of you to keep investigating, keep letting go of your fear. Remember that fear of death is the same as fear of life. What are we afraid of? When we deeply feel and, at the same time, truly know that experience we can come to joy. It is still possible to live fully as a human being, completely accepting our pain; we can grieve and yet still rejoice at the way things are.

By

Ayya Medhanandi

Comments

Post a Comment